.

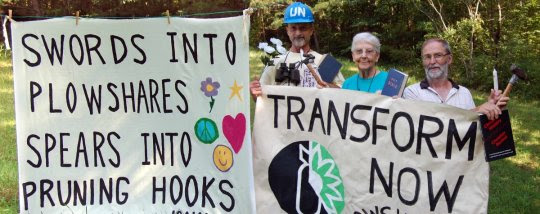

Protests over discrimination against Dalits in Nepal

are delivering little.

Credit: Mallika Aryal/IPS.

Protests over discrimination against Dalits in Nepal

are delivering little.

Credit: Mallika Aryal/IPS.

She screamed. Locals came to her rescue and the attempt was thwarted.

Sarki recognised the voice of her attacker as that of a neighbour and filed a

police complaint.

Sarki recognised the voice of her attacker as that of a neighbour and filed a

police complaint.

The next day Sarki was met by a mob, led by her alleged attacker, at the

village market. She was called derogatory names, her clothes were torn,

and soot was smeared on her face. She was garlanded with shoes, beaten,

and paraded around town. After the incident, Sarki fled the village.

village market. She was called derogatory names, her clothes were torn,

and soot was smeared on her face. She was garlanded with shoes, beaten,

and paraded around town. After the incident, Sarki fled the village.

In Dailekh in western Nepal, Sushila Nepali, 28, was raped by a local

schoolteacher for years. She was forced to abort twice, but got pregnant

again and gave birth to two children. Disowned by her family, Nepali has

been living on the streets and begging for shelter and food.3

schoolteacher for years. She was forced to abort twice, but got pregnant

again and gave birth to two children. Disowned by her family, Nepali has

been living on the streets and begging for shelter and food.3

Sarki and Nepali are from different parts of the Himalayan nation, but

what is common between them is their caste group - both belong to the

socially marginalised Dalit community. Sarki's attacker and Nepali's

rapist were both high caste Hindus.

what is common between them is their caste group - both belong to the

socially marginalised Dalit community. Sarki's attacker and Nepali's

rapist were both high caste Hindus.

There are an estimated 22 Dalit communities in Nepal. Researchers and

Dalit organisations say they make up 20 percent of the country's 27

million population. Dalits are considered to be at the bottom of Nepal's

100 caste and ethnic groups.

Dalit organisations say they make up 20 percent of the country's 27

million population. Dalits are considered to be at the bottom of Nepal's

100 caste and ethnic groups.

They bear a much bigger burden of poverty, with 42 percent Dalits under

the poverty line as opposed to 23 percent non-Dalits.

the poverty line as opposed to 23 percent non-Dalits.

After a long political impasse, Nepal went back to polls in November.

After two long months of negotiations, new assembly members are now

finally sitting down and writing a new constitution. But experts say even

in the new assembly, the Dalit community is the most under-represented,

with only seven percent, or 38, of the 575 Constituent Assembly members

being Dalit.

After two long months of negotiations, new assembly members are now

finally sitting down and writing a new constitution. But experts say even

in the new assembly, the Dalit community is the most under-represented,

with only seven percent, or 38, of the 575 Constituent Assembly members

being Dalit.

Rajesh Chandra Marasini, programme manager at the Jagaran Media

Centre, an alliance of Dalit journalists formed to fight caste-based

discrimination, worries that Dalit related issues would, once again,

not get priority in the new constitution.

Centre, an alliance of Dalit journalists formed to fight caste-based

discrimination, worries that Dalit related issues would, once again,

not get priority in the new constitution.

"I am concerned that the new Dalit assembly members would take the

party line and become a mere physical presence," he told IPS. "I fear

that Dalit advocacy would become an afterthought."

party line and become a mere physical presence," he told IPS. "I fear

that Dalit advocacy would become an afterthought."

Nepal's Civil Code 1854 had legalised the caste system and declared the

Dalit community as ‘untouchable'. In a Hindu hierarchical structure,

such a label dictates where Dalits can live, where they can study and

where they can socialise.

Dalit community as ‘untouchable'. In a Hindu hierarchical structure,

such a label dictates where Dalits can live, where they can study and

where they can socialise.

In 1963, caste-based discrimination was abolished in Nepal and the

National Dalit Commission was formed. In 2011, the Caste Based

Discrimination and Untouchability Act was passed.

National Dalit Commission was formed. In 2011, the Caste Based

Discrimination and Untouchability Act was passed.

Yet, Dalits continue to be marginalised.

"Violence against the Dalit community is ignored or often goes

unreported and unnoticed in Nepal," said Padam Sundas, chair

of Samata Foundation Nepal, a research and advocacy organisation

that works for the rights of the marginalised community in Nepal.

unreported and unnoticed in Nepal," said Padam Sundas, chair

of Samata Foundation Nepal, a research and advocacy organisation

that works for the rights of the marginalised community in Nepal.

Dalits are still barred from community activities such as worshipping

in same temples as higher caste Nepalis. The higher castes don't eat

the food touched by members of the Dalit community or even use

the same community tap that Dalits use for water. And women are

the worst affected.

in same temples as higher caste Nepalis. The higher castes don't eat

the food touched by members of the Dalit community or even use

the same community tap that Dalits use for water. And women are

the worst affected.

"Dalit women are at the bottom of the caste and gender hierarchy

in Nepal," said Bhakta Bishwokarma, president of the Nepal National

Dalit Social Welfare Organisation (NNDSWO), which works to

eliminate caste-based discrimination in Nepal.

in Nepal," said Bhakta Bishwokarma, president of the Nepal National

Dalit Social Welfare Organisation (NNDSWO), which works to

eliminate caste-based discrimination in Nepal.

"Dalit women's suffering is triple-fold - society discriminates against

them because they are women, then they are discriminated against

because they belong to the Dalit community, and within their own

community they suffer all over again for being women," Bishwokarma

told IPS.

them because they are women, then they are discriminated against

because they belong to the Dalit community, and within their own

community they suffer all over again for being women," Bishwokarma

told IPS.

Women's rights activists say Dalit women are the most vulnerable.

"If you study the cases of women who are accused of being ‘witches',

they are usually Dalit women. They are the ones to be trafficked easily,

they are the ones who work in terrible conditions," said Durga Sob

of the Feminist Dalit Organisation (FEDO) that works closely with

the government on Dalit gender issues.

they are usually Dalit women. They are the ones to be trafficked easily,

they are the ones who work in terrible conditions," said Durga Sob

of the Feminist Dalit Organisation (FEDO) that works closely with

the government on Dalit gender issues.

Activists say when Dalit victims of violence want to file a police complaint,

they are discouraged.

they are discouraged.

"They are told that getting the law enforcement authorities involved

would disturb social harmony, and victims are encouraged to

informally reconcile," said Bishwokarma. "No one is held accountable

for any discriminatory acts against Dalits."

would disturb social harmony, and victims are encouraged to

informally reconcile," said Bishwokarma. "No one is held accountable

for any discriminatory acts against Dalits."

News of the attack on Sarki received wide media coverage, and the

attack and was severely condemned. A few days after the story broke

activists gathered in front of the offices of Nepal's policymakers and

organised a protest. It saw a handful of women's rights activists and

allies standing with banners, demanding that the government act.

attack and was severely condemned. A few days after the story broke

activists gathered in front of the offices of Nepal's policymakers and

organised a protest. It saw a handful of women's rights activists and

allies standing with banners, demanding that the government act.

"The activists stood there for a few days, handed a memorandum to

the government and the issue died down," said Bindu Thapa Pariyar

of the Association for Dalit Women's Advancement of Nepal (ADWAN).

the government and the issue died down," said Bindu Thapa Pariyar

of the Association for Dalit Women's Advancement of Nepal (ADWAN).

Researchers say there are major reasons why Dalit issues don't get

noticed.

noticed.

"We have all kinds of acts and laws in place, but they are never

implemented and even when we have tried to implement them,

victims don't get justice," said Sob of FEDO.

implemented and even when we have tried to implement them,

victims don't get justice," said Sob of FEDO.

She recommends that the legislation be made simple and local law

enforcement authorities be trained, so they understand the rights

of Dalit people.

enforcement authorities be trained, so they understand the rights

of Dalit people.

Some activists say the Dalit movement has lost its momentum.

"We cannot think of Dalit activism with a ‘donor supported project

implementation' approach," said Pariyar of ADWAN. "When the

project money runs out, we move on but that doesn't necessarily

mean we have achieved what we set out to do."

implementation' approach," said Pariyar of ADWAN. "When the

project money runs out, we move on but that doesn't necessarily

mean we have achieved what we set out to do."

In Sarki's case, for instance, there were issues of her rehabilitation,

psychological trauma counselling, the safety of her family and her

safe return home.

psychological trauma counselling, the safety of her family and her

safe return home.

"Rights activists need to think long-term, a protest only nudges

policymakers, real work happens with the victims in the field,"

said Pariyar.

policymakers, real work happens with the victims in the field,"

said Pariyar.

She calls for a stronger leadership in Dalit advocacy.

"The Dalit lawmakers may be under pressure from their parties,

but we need watchdogs outside the assembly so that we can keep

pushing them to make the right decision," said Pariyar.

but we need watchdogs outside the assembly so that we can keep

pushing them to make the right decision," said Pariyar.

"If we don't push now, when a new constitution for the nation is being

written, we will never do it," she said.

written, we will never do it," she said.

© Inter Press Service (2014) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service